和孤獨對望的是熾烈。

Where Fervor Meets Solitude.

.png)

1

In numerology, 7 represents solitude and loneliness, while 5 represents passion and wandering.

I'm someone who has a whole row of 7s — and quite a lot of 5s, too.

2

As a child my father would make me perform circus-like tricks. With an air rifle, for instance, I could knock a fifty-cent coin from the mouth of a bottle a few meters away. The bottle never broke. I never practiced; it was pure instinct.

In 1975, after I went to Paris, I got a gun license and went to a police shooting range. Every cop would stop and watch. I used a Beretta: out of fifteen shots, twelve or thirteen would hit the bullseye.

Almost everything I've done in my life, I learned outside of formal training — shooting, guitar, photography. I was nineteen, still studying at Shih Hsin College, when I bought my first second-hand Nikon F camera. I didn't even know how to load the film, but I just grabbed the camera and started taking strange pictures.

The one thing I learned through formal training was high-speed driving.

I learned anti-tracking techniques in Paris. The course was very expensive. Like a movie stunt driver, I was trained to the level where I could protect important people in an emergency by spinning in place or executing power slides.

Until I returned to Taiwan at the age of forty-three, there was always a rifle by the bed in my Paris apartment. I also kept a loaded handgun in my car, hidden underneath a leather jacket on the passenger seat.

When I felt an inexplicable restlessness—my body like a bullet fiercely burning but unable to fire—I would jump in the car and speed away.

3

My interest in photographing women, and nude women, all began in Paris.

During my aimless days in Paris, I met a very beautiful girl at a cafe near the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés.

One day, as we were standing on the street, a bus drove by with a huge advertisement featuring her face. That's when I learned she was a somewhat well-known model in Paris. She convinced me to give up my dream of filmmaking and introduced me to a job as a photography assistant.

While working in the studio, I also shot my own stuff. On my days off, I would personally take my slides to important publishing houses or magazines. Rookie models get rejected nine times out of ten—and so did I. But I kept trying, until one day the art director of ZOOM magazine agreed to see me and published eight to ten pages of my work.

Just like that, I became what you might call "famous." Offers came in from all directions, and I got my own agent, studio, and assistants.

The photos I took in Paris were all related to commercial and fashion work. Because of fashion, I had the opportunity to photograph many top models and special subjects.

Even so, I still maintained my own style—one very different from the mainstream commercial photography of the time. I accumulated a lot of photos back then.

When the Japanese magazine Asahi Camera featured my work, they chose some of my more "strange" images—for example, a girl lying on the floor with her pants half down, watching TV; or a nude woman with beautiful breasts, her eyes covered.

I wanted to bring a sense of the "abnormal" into my photographs — to create visual experiences that felt unsettling, yet alive.

After returning to Taiwan, I devoted myself purely to creative and artistic work. For a long time, I avoided photographing people, deliberately avoiding human elements. When people did appear, they were like passersby or hikers, never the focus. After spending years surrounded by beautiful men and women from morning to night, I naturally wanted to break away from that world when it came time to create something of my own.

My "Series of Grass" began this way, in Tainan. Alongside it, I also created an unpublished series. A very good female lawyer friend of mine had a serious illness and asked me to photograph twenty cancer patients in the hospital. That body of work was never published; it remained a documentary record made out of a sense of duty.

It wasn't until I started collaborating with Jamei Chen that I began photographing people again. My work gave me countless opportunities to be around models, and I began photographing women again—sometimes also shooting my own projects on the side. It was an organic, gradual development.

4

There's a saying that everyone on the road is lonely.

As for me, I choose to keep rolling forward in solitude — whether I'm on the road or not.

So, inevitably, I have many "7s" in my life. They are everywhere.

But the lonely 7 is often my lucky number. I've pulled "777" on a slot machine. Once, I even won nearly two million Taiwan dollars betting on "17" at a roulette table.

I was in Monte Carlo accompanying an elder to a conference, helping with driving and translating. After I dropped him off, I snuck over to the casino across the street. I didn't have a suit, so I couldn't get into the main gambling hall and had to play roulette in the smaller room next door.

I exchanged five hundred euros. I lost fifty first, then another hundred, and with the remaining three hundred fifty euros, I put it all on one number—17.

I won. But just then, my pager went off, so I stepped out to the door for a moment. The casino staff thought I was a Japanese tourist and tried to take advantage of me when I left the seat. According to the rules, they should leave the original three hundred fifty that I bet on the table and pushed the winnings to the side. But they didn't — they kept stacking all the chips on number 17.

But when I came back, 17 hit again! So I won nearly two million Taiwan dollars in a single go.

In fact, since I first entered a casino around the age of twenty-six or twenty-seven, I've never lost money gambling in nearly fifty years. Whether it's the illegal slot machines in basement coffee shops in Taiwan or casinos abroad, I never lost money.

7 is a lonely and solitary number, but also a mysterious one.

5

I also have a lot of 5s. 5 is about wandering, but also passion and intensity, the pursuit of pleasure.

That's why I am absolutely not suited for marriage. I can't stay with one person from beginning to end in an orderly way. I've wronged my partners.

Even though the passion has faded now, it was truly overwhelming in my younger days.

Ever since I first became sexually active, I've always been the type of person with a vivid imagination and daring spirit. By "imagination," I mean I could think of all sorts of different spaces and ways to engage in sex. By "daring spirit," I mean I had the nerve to try it in places where one "shouldn't be doing such things."

For example, in Paris, one time while eating at a restaurant, a girl just started things under the table. The tablecloth was very long, so she got underneath, and no one outside could see anything. I've also tried it in movie theaters and cafes.

Comparing with other forms of pleasure—fast driving, shooting, playing with weapons—those are rigid thrills, charged with danger and violence.

Sex, on the other hand, is a softer kind of pleasure; you need to find comfort and fun within that softness. It requires focus, but unlike shooting or racing, it doesn't call for totalizing tension.

For me, the pleasure of sex is like a perfect "endpoint"—like winning at gambling, finishing a moving film, or tasting an exquisite dessert. It brings a deep sense of satisfaction, a pleasant feeling of "completeness." A good sexual experience lingers in memory.

In Paris, I knew a few beautiful women who loved mountain climbing. After one of them went on a high-altitude trek, she wanted to go back every year or two. That's because she met a guide who, at night, while they slept, would lick her from her toes all the way to her head, made her climax. Some women don't even need intercourse to have an orgasm; just that is enough. When she returned to Paris, she could never find that feeling again.

I still remember the way she told me the story over dinner — almost drooling as she spoke.

Compared to girls in Taiwan or the East, French women place great importance on sex. If a husband or boyfriend can't satisfy them, they will leave immediately, no question.

Some women have never had an orgasm in their lives—that's the man's fault.

To be a good lover, a man must first be considerate, generous, and have a sense of humor; above all, he can't be selfish in bed. I'm not very good with sweet talk, but I always do what should be done. On birthdays and holidays, you take her out to dinner; when making love, you make sure she's satisfied.

Many men are selfish; they just lie in bed expecting the woman to serve them, and then they leave when they're done. A truly successful sexual encounter is one where you take care of the other person both before and after. That's a more complete sexual act.

6

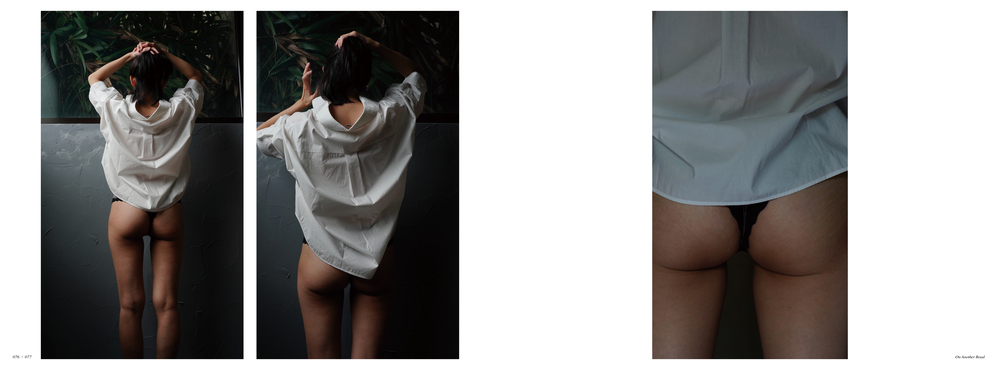

This book contains many women, nude women. But it is not a record of my romantic relationships.

Some are my very good female friends; some are more than that. All I want to say that I remember the women I encountered along the landscape of my life, and I've brought them all into my work.

There are many photographers who photograph women and nudes. I envy Nobuyoshi Araki's sense of "it doesn't matter" — that complete indifference, that freedom from care. But the women I photograph in this book, I want them to carry a feeling of love.What I mean by a "feeling of love" is that even if there isn't real love, I can create an atmosphere of love. Some of the photos were taken in hotels or inns, not for that purpose, weren't but simply because those places offered freedom — and running water.

Why do I emphasize a "feeling of love"? Because there's already plenty of excellent fashion photography and body-light-and-shadow work out there. And when it comes to the bizarre or provocative, there are masters like Helmut Newton and Guy Bourdin. I feel that all I can do is find a small space in between — a gap or niche where something of my own can exist.

There's an interesting thing about this. Most relationships between photographers and models are rather strange — outside of work, other things can happen, and they end up taking some unusual photos. But those photos often don't serve any purpose at the time. Many world-class photographers, especially in the fashion world, later publish their own photo books — and more than seventy percent of the images in them are works that magazine editors once rejected, afraid to use.

Under that system, the negatives belong to the photographer, so when they eventually publish their own books, most of the photos come from those "unused" shots — often because they were too explicit or too strange.And there aren't many examples of photographers using a "feeling of love" when photographing women. Kishin Shinoyama's Water Fruit featuring Kanako Higuchi is one of the few examples.

Speaking of the "feeling of love," love, for me, often cannot be turned into a picture. I believe that sex and love can be completely separate. Sex is easy, but love is not.

Love involves longing, attachment, and that feeling that can make you cry. And with many of my lovers, I couldn't capture that kind of intimacy.

Sometimes, people who aren't lovers, just female friends, or even just sexual partners, can spark a stronger creative impulse. On the other hand, I have very close female friends whom I've never been able to take a single good photo of in my entire life.

The outcome is never certain.

7

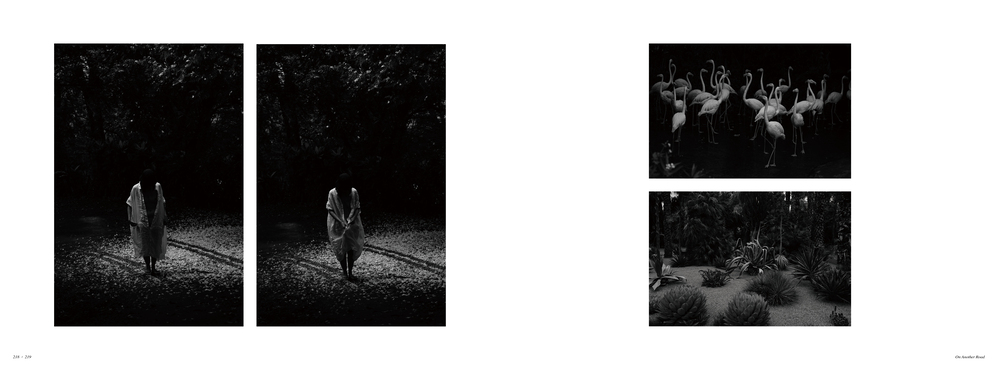

I never create my work for a specific purpose or for a publication or exhibition.

My life is like a big chest of drawers. Every time I take photos, I just toss them in there. Maybe, five or ten years later, someone will suddenly say, "Hey, let's make a book." Then I'll go through the drawers, select and rearrange the photos, give it a name, and make them a book or an exhibition.

This time, the way of the pictures arrangement in this book gave me a very different feeling about my own work—something I've never had this experience before.

In the past, whether in magazines or exhibitions, my photos were displayed on very large pages. The photos were also processed a bit too cleanly, almost with a sense of fastidiousness.

The way my work was treated this time, I had never seen it like this before, and it made me confront myself anew. It wasn't just because the pages were smaller, requiring closer inspection, but also because the sequence of many photos allowed me to see the connections between them.

I hope readers will find these women beautiful, sensual, striking, and unique — not the kind of images where models pose awkwardly, nor those that verge on the pornographic.

I believe beauty absolutely exists, and within it there are traces of my essential elements: a sense of distance, touches of the surreal, and even hints of absurdity. For me, sharing these works with readers is about letting you feel what it's like to hold the book in your hands — to turn its pages and know that the photographs belong to you, that they're not something abstract or intangible.

All the loneliness and solitude, the passion and wandering—they are not far from you.

And perhaps, through that closeness, you might experience another kind of comfort and healing.

This might be the hope I hold, as someone who always takes another road.